What is Open Data and Open Licensing?

While the idea of open data has remained somewhat abstract in popular media, proponents of the movement have conceptualized it in distinct ways. Some of these ways include common phrases used by open data stakeholders, such as “Free Our Data” and “Knowledge for Everyone”. Such political- or commercial-sounding slogans may be catchy, but they tend to essentialize the Open Data Movement as a uniform, democratic undertaking. Other keywords used in conferences, scholarship, and on various government and activist websites include transparency, accountability, participation, innovation, and democracy. The Open Data Movement has also been associated with the Data Revolution, referring to the vast amount of information society began to produce in the twenty-first century. This revolution was compared to other significant transitions in history, like the advent of the printing press or Renaissance navigation (Kitchin, 2014). Currently, the described benefits of the Open Data Movement are often tied to economic growth and the “opening up” of governments and scientific research. The movement is thus part of a wider rhetoric and imaginary used to earn universal support. Some have argued that such an uncritical conceptualization of open data can conceal potential legal, political, and ethical concerns (Kitchin, 2014).

The roots of the Open Data Movement can be traced to the Western scientific community of the early twentieth century. In the 1940s sociologist Robert King Merton popularized the idea that scientific research should be made free to all (Data.gov, 2013). For the sake of scientific progress and the idea of “common good”, the public availability of scientific research thus became a popular cause within academia.

Beyond scientific research, the case for open data grew alongside other “open” movements, such as open-source software in the 1950s and 60s and the implementation of Access to Information Acts by various nations. In the last four decades, the case for open data reached some important milestones, with Ronald Reagan making the United States’ GPS (Global Positioning System) technology available to citizens in 1983. The term open data was first used in 1995 by an American scientific agency (Chignard, 2013), and in 2013 Barack Obama signed an executive order making all federal data public (with some exceptions).

Since the 1990s the Open Data Movement has gained significant momentum due to advocacy groups and government initiatives. One of the defining moments of open data came in the relief efforts for Hurricane Katrina in 2005, when volunteers gathered and shared valuable information from government websites such as building permits and population estimates (Sollazzo, 2015). Today, the Open Data Movement continues to redefine itself and can be commonly experienced in daily life in the form of Google Maps or Wikipedia.

Data for Humans and Computers

Data is a fuzzy concept—a definitive definition is nearly impossible to come by—and the difference between data and information, knowledge, and wisdom is a matter of philosophical dispute.

Anything that says something about the world is a piece of data. Anything that can be sensed or measured can be considered data, whether by our human senses, or by machines. This is similar to how your eyes apprehend sensory data about colour, size, shape, location and movement; how scales measure weight, and how smart phones store data– some of which is displayed as text, phone numbers, or photos.

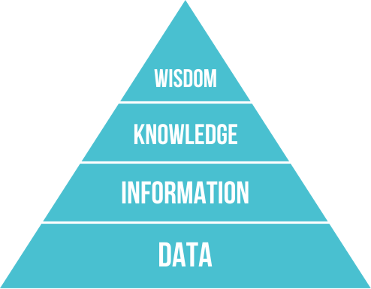

The DIKW Pyramid is a way of understanding how data, information, knowledge and wisdom are related to each other, and to the decisions that people make every day. In the DIKW pyramid, data is the most basic thing, usually referring to simple facts or descriptions, like the name and location of a restaurant. Information is contextualized data, like that the restaurant is walking distance from where you are. Knowledge and wisdom are even more contextualized, like knowing that this restaurant is the best of its kind in the neighbourhood, or that certain dishes live up to the hype while others do not.

But this description of data as ‘out in the world’ is only half the picture—data is often considered ‘theory-laden’ by scholars, meaning that every piece of data is also related to a concept. As a result there is no “pure” data. Think about colour; data about colour only has meaning if we have words to describe it, and might change if we have new words. For example, if you knew only 16 colours, you might call this one green—but if you knew 256 colours then you might call it teal. Imagine if you didn’t know any words for colour!

Computers provide a particularly good example of why concepts are important. Most computers store data digitally in the form of binary code—huge collections of 1s and 0s. As 1s and 0s this data is meaningless to humans, and it is meaningless to computers unless they have instructions that tell them what to do with it. When sections of those 0s and 1s are looked at together with concepts, they have meaning. Just as data needs concepts to have meaning, they also need context to be meaningful.

Closely tied to structured and unstructured data is the idea of readability. We say that data ‘human-readable’ if they can easily be read by people– like text in sentences and paragraphs, but also numeric data in tables. Humans can often understand things that are human readable even if they’re not told exactly how to understand. Machines, on the other hand, require very specific instructions to know what do with information. This is why ‘machine-readable’ information has to be structured.

Changing the context, by expanding it for example, can reveal data’s different aspects. For example, if I say your favourite hockey team lost, you might feel one way—but if I mention that many of the players had been injured or sick before the game, you might feel a different way. Some common ways, or formats, that we interact with digital data include text, numbers and true/false values. If you’ve ever tried opening a file without the proper program, you’ve experienced something akin to your computer not having the concept for some data.

File Formats

File formats are agreed upon and standardized ways information is encoded for use by computers. A format describes how the file is represented when stored. Files end in extensions (for example: .mp3, .html, .doc) which usually are shortened versions of the format name.

| Format | Description |

|---|---|

| .xml (Extensible Markup Language) | A language for describing text-based data using tags. XML can be read by both humans and machines, and is based on open and free standards. |

| .csv (Comma Separated Values) | A human-readable format used to store tabular data as text that can be understood by many different programs, and is often used as a way to interact with information across software applications (data-interchange). |

| .json (JavaScript Object Notation) | Another human-readable data-interchange format based that stores information about objects in ‘pairs’ of an attribute name and value. |

| .pdf (Portable Document Format) | An very common, and open (as of 2008) format for document presentation independent of the application or devices used to access it. A .pdf contains all of the information needed for a pdf reader to display it. A PDF may or may not be machine readable. |

| .rdf (Resource Description Framework) | A standardized framework for conceptually modelling semantic (human readable) information about almost anything. |

| .kml (Keyhole Markup Language) | A special version, or extension, of XML used specifically for geographic information and linking coordinates on a map to information, like a specific place, or attribute. Originally developed by Google for Google Earth. |

| .doc(x) (Open Office XML) | An extension of XML for displaying and editing Microsoft Word documents. Can be read by some other programs. |

| .xls(x) (Open Office XMP Workbook) | An extension of XML for displaying Microsoft Excel Documents, which can be read by some other programs. |

| .shp, .shx, .dbf (Shapefile) | Shapefiles are a groups of files used to describe geospatial features in terms of points, lines, and areas (polygons). They often come in a compressed folder (.zip) and are not readable by humans unless working with a geographic information system (GIS) program. |

STRUCTURED DATA

All data contained in files is structured in some way (see file formats and data for computers, above), however ‘structured data’ refers specifically to agreed upon and standardized ways of storing data so machines can read it and use it in a consistent way. Typically this means data resides in fixed fields in a repository.

OPEN FORMATS AND STANDARDS

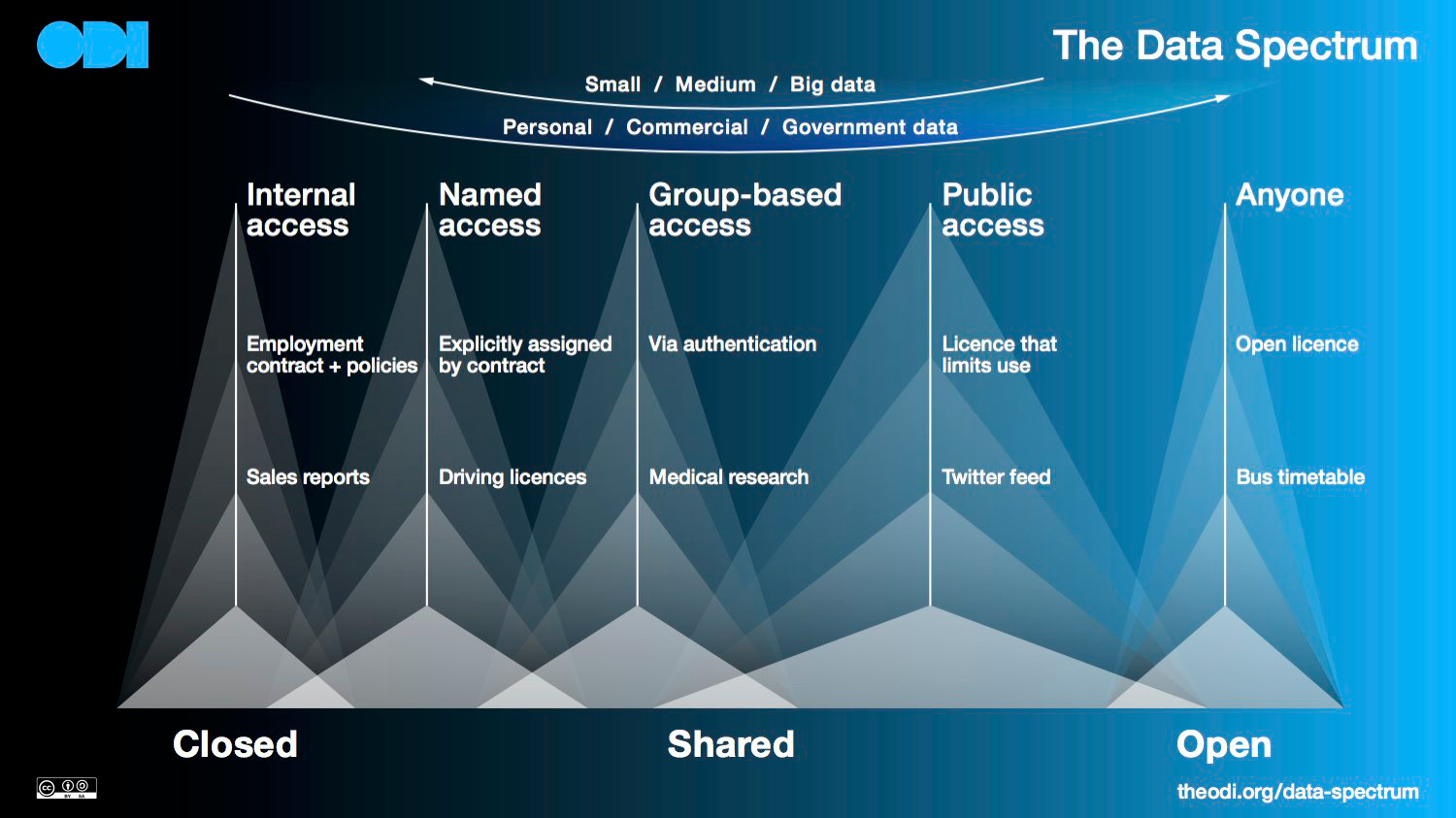

The Open Data Institute’s Data Spectrum treats Openness as a matter of degree along with the type of data and the size of the data set. When data is the kind that many people might make useful information out of, it is better suited to being open: especially if it is not personal or commercial, and could pose risks if it was released.

The things we do with files every day are only possible because of the ability for different programs and files to talk to each other. File formats use specifications to accomplish this. While specifications that allow programs and files to interact may be published, they are not the same as an open or free file format. An open format refers to a format where not only the specification, but also that the intellectual property rights (described by the license) are Open (see Open Licenses below). Some examples of open formats include .zip for storing compressed files and .flac for audio files. As an aside, not all formats that are open started out that way: .pdfs and .gifs, both very popular, were originally closed formats.

Open Data standards describe and govern the way that types of OD ought to be released. These standards include best practises to ensure that OD sets can be effectively combined with other data (so that OD sets are interoperable) and that OD was generated with appropriate measurements and categories (so that when people create OD sets they measure the same things in the same ways). For more on the importance of interoperability as a key benchmark for OD, see Geothink’s project and white paper on OD standards.

Standards for openness are created and maintained by international organizations like the International Organization for Standardization, which standardizes file formats, World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) which publishes documentation on best practises for Open Data publishing, and the Popolo project, which is specifically geared toward standardizing Open Data metadata, in order to make it easier to compare similar data from different jurisdictions. Whether governments make their Open Data conform to these standards is another matter entirely.

Open and Closed Licenses

A license is a legal document that outlines what people are able to do with a work, project, or collection of information. Licensing for Open Data can apply to the data set itself, applications that make use of the data, or even the material on the website or portal where that open data is accessed.

License conditions usually identify the following about a work:

- who should be attributed as the creator, if anyone

- whether or how it can be used for commercial purposes by others

The license conditions could also let you know:

- how any project that makes use of the work should be licensed

- whether it must be done in an open manner

Licenses can also be political, revealing ideological divides within communities. For instance, distinctions between Open Source and Free Software are often revealed through the selection of closely related, but importantly distinct, licenses. Adding an open license to a work can be used to publicly indicate membership and participation in the Open Data community.

Open licensing is the practice of using a license that allows for more permissive distribution and modification of a work, such as a data set or a program. Open licenses grew out of Lawrence Lessig’s idea of ‘Copyleft,’ a form of licensing that takes advantage of existing copyright law to achieve the aims above (Copyleft, 2015). The Open Knowledge Foundation identifies licenses that meet it’s open definition, including the Open Government License Canada 2.0 (Conformant Licenses, n.d.).

Within Open Data two popular licenses are ODbL and Creative Commons, however there are other licenses that are also ‘open’ that cover specific types of works, like software code. Licenses that are not considered open are generally called closed, or Proprietary.

Why People use Licenses

The most basic reason for licensing may seem a bit counter-intuitive: if you don’t choose one it will be done for you! The way copyright law works in Canada, any “original work” you create is automatically covered within a license framework providing for ‘economic and moral rights,’ including the right to receive payment and protect how that work is used. If you want to allow as a default, a different or broader range of ways for people to use your work, you should take the time to choose a license!

OPEN GOVERNMENT LICENSE CANADA 2.0

The Canadian Federal Government has developed its own license to release data under (Government of Canada, 2015b). It provides much the same provisions as other open licenses, but is only used by the Canadian Government.

CREATIVE COMMONS

Creative Commons is a US-based nonprofit that has created copyright license templates and other tools to enable the public to more easily share and use creative works (About, 2007). Abbreviated as “CC,” Creative Commons licenses allow for rights holders to decide if the work needs to be attributed (“BY”), whether it should not be used for commercial means (“NC”) and whether it must be shared using the same license (“SA”). These different licenses all use the existing framework of copyright law!

ODbL

The Open Data Commons ODbL or Open Database License is an open license that covers copyright and also rights specifying how content from a database can be extracted and reused. Given the complicated nature of legal frameworks in different countries around the world, there are challenges in how it can enforce conditions on all future reuse. For more see the Open Data Handbook glossary.

PROPRIETARY

Proprietary licenses (originally referring to software licenses) is a term from software code development. It refers to licenses which restrict redistribution and modification of a work, as well as potentially other uses, or requires permission to be obtained. It is considered ‘owned’ by the individual or company and ‘closed’ as a result (Free Software Foundation, 2016).

Choosing a License

Choosing an open license can seem daunting, however many people have faced the same challenge and you can rely on the work that they have put in before! Various services, guides, and websites exist which walk you through the process of choosing a license based on your content. An example of two popular open license pickers are: choosealicense.com and Creative Commons’ selector.

While these resources can be helpful, it is good to pay attention to who has created the tool you are using. For example, GitHub, which runs choosealicense.com, is a for-profit that has built its business around promoting open source. They benefit from a commercialized open source ecosystem, whereas other proponents of open licensing would like it to remain non-commodified.