Open Data and Privacy

The practice of proactively releasing government data poses many opportunities to society. According to Critical Data Studies scholar Rob Kitchin (2014), open data democratizes information as opposed to “confining the power of data to its producers and those in a position to pay for access” (p. 48). Despite its benefits, open data initiatives can also pose a threat to the privacy of individuals. Specific, detailed, and granular data enable businesses, policy-makers, researchers, and the public to conduct rich analysis, and to apply evidence-based decision-making (Green, Cunningham, Ekblaw, Kominers, Linzer, Crawford, 2017). However, this detailed data can be used to identify individuals, posing a threat to their privacy. As a result, government bodies are tasked with the challenge of striking an appropriate balance between the utility of open data and the privacy of the data subjects.

This relationship is especially important due to the larger implications it poses to citizen trust and confidence in government. If citizens feel that their privacy has been breached through an open dataset, they may feel betrayed or lose trust in their government. For instance, confidentiality in census reporting has been upheld by statistics offices, otherwise they risk false responses by the public (Borgesius, Gray, Eechoud, 2015, p. 2089). Obfuscation is a privacy-preserving function that results in false responses, and therefore undermines the integrity and utility of the data. It is important for open datasets to uphold privacy in order to maintain public support and trust in government services, and in turn allow for accurate data reporting to persist. This is one of the many benefits of having on-going consultations with the public, in addition to keeping the public informed of open data practices and considering their input (Zevenbergen, Brown, Wright, Erdos, 2013, p. 6).

Different actors within society may also use open data to advance their own interests. Open data can be understood as a power relation between citizens and government. Ian Hacking describes the erosion of determinism and the avalanche of enumeration in society in the nineteenth century, where laws based on statistics were used to define a central tendency in society and the outliers were classified as pathological (Hacking, 1990, p. 2). Particular types of activists may be interested in protecting their privacy in order to maximize their autonomy from the state, and use open data as a mode of government accountability to maximize their control over the state (“Open Data & Privacy”, 2013).

Businesses may use open data to inform analysis that advance their commercial interests. They may use this data to inform consumer profiling or geographic red-lining, a practice where services are strategically denied to people in specific areas based on the racial composition or socio-economic status of the area. Data brokers also collect information about individuals to inform credit score calculations and online behavioural advertising. A government’s decision to make a particular dataset open has important implications for privacy as seemingly non-personal data can have characteristics or attributes that allow for an individual to be identified after the fact, even if that data had already been anonymized (Jaatinen, 2016, p. 31). As discussions surrounding blockchain and other public-ledgers persist, and detailed data collection capabilities are introduced through smart cities, it is imperative that privacy be considered at the outset of data collection.

Privacy Risks of Open Data

There are many ways in which the privacy of individuals can be violated by open data initiatives. Open data shouldn’t, and generally doesn’t, include the personal information of an individual. However, if enough attributes about an individual are released, it is possible that their identity can be inferred. This can be accomplished by cross-referencing and connecting data between different databases and datasets. The falling costs of data collection and advanced analytical methods such as big data, have posed new threats to how information can be identified and connected to specific individuals. In the wake of these advanced techniques, Helen Nissenbaum (1998) argues that individuals do indeed retain a right to privacy in public realms, as people do not expect that others will document and analyze their behaviour in a fashion consistent with advanced analytics techniques (“Privacy in an Information Age”, p. 595). Therefore, the collection and aggregation of “public” data found in open datasets and other databases can violate the privacy of individuals by painting a vivid picture of them without their consent or reasonable expectation.

Once information is attributed to an individual, it meets the definition of personal information under Canada’s federal privacy legislation. However, despite the protections that privacy laws give to individuals, privacy breaches can still occur. In those scenarios, personal information is exposed and the damages incurred can rarely be remedied given the speed in which information is shared on the Internet. Open data is accessible to people around the world and it would therefore be difficult to know if an individual’s personal information was retained by others on the Internet. It is therefore important for the person or entity that processes personal data, known as the data steward, to protect the personal information of the public at the outset when releasing open data (Cate, Cullen, Mayer-Schonberger, 2013, p. 13).

It is also a privacy risk when data is used for purposes unrelated to the dataset’s objective. One of the main goals of open data is to improve the social well-being of citizens by improving the delivery of public services and informative research. The use of advanced analysis techniques on open datasets by any public or private actor opens the possibility for privacy breaches to occur. It is therefore important that governments collect and distribute as little personal information as required to fulfill the goals of the collection and to avoid storing an excess of personal information (“Open Government and Protecting Privacy”, 2017, p. 6). Minimal data collection is an important first step in preventing privacy breaches.

Legal and Legislation

n Canada, privacy laws exist to help safeguard the personal information of the public. The Privacy Act is Canada’s federal privacy legislation that governs how the federal public service manages personal information. Each province and territory in Canada also has its own privacy legislation that governs how personal information is managed within its own government. Despite the safeguards that the Privacy Act and its provincial counterparts provide, they do not address the specific challenges posed by open data initiatives. Legislation that provides a specific framework or method in the adoption of open government initiatives has yet to be introduced (“Open Data, Open Citizens?”, 2016). As a result, there is no clear consensus on the steps or procedure that should be required to ensure privacy protections are applied before data are released (Green et al., 2017, p. 3). On an international level, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) has outlined a set of 8 basic privacy principles that should be considered when a researcher, government institution, or other actor collects and retains personal information. These privacy principles include: 1. limiting the collection of personal information; 2. ensuring accuracy and completeness; 3. specifying the purpose for which data are collected beforehand; 4. using the data only as specified; 5. protecting data with reasonable security; 6. openness in data practices and the identity of the data steward; 7. individual participation in their data; 8. and accountability of data owners to the above principles

These principles lay an important foundation for how data should be managed. They are integrated into privacy law in Canada, however many other OECD member countries have yet to do the same (“OECD Guidelines”, 2013).

Territorial Jurisdiction

Given that open datasets are made available on the internet, they are accessible by individuals all over the world. Privacy on the transnational Internet is therefore difficult to protect with laws that govern specific jurisdictions. Basic international law principles decree that countries may not apply their laws outside of their borders (Scassa, 2015). However, in some cases, extended territorial jurisdiction may allow a country’s laws to extend beyond their borders when the activity is closely connected to that country (Scassa, 2015). This was demonstrated by the Privacy Commissioner of Canada in its recommendation to the Romanian company Global24h, which used public court data in Canada to create a searchable database of cases (Scassa, 2015). Despite this exception, a foreign national whose privacy had been violated in an open dataset would have a difficult time finding recourse to protect their privacy from abroad. The territorial limitations of privacy law also reinforce the need for privacy to be considered as an initial phase in open data programs.

Public Information & Access to Information:

It is important to draw a distinction between open data and public data. Public data may intentionally disclose personally identifiable information to achieve a particular policy objective. For example, the Ontario Sunshine List is a public dataset that includes the annual salaries of publicly employed individuals who earn more than $100,000 (Crawley, 2017). The classification of public data would normally be considered a pre-condition for open data, however not all government data can be open due to intellectual property and privacy concerns (Jaatinen, 2016, p. 34). The format in which the data is presented is therefore very important in distinguishing public data from open data. Open data has specific formatting requirements in order for data to be machine readable by the majority of computers. In the Globe24h case, the Privacy Commissioner recognized that the company violated the privacy of Canadians by manipulating publicly available case judgments into a database. This recognition demonstrates an alignment of the law with Nissenbaum’s “privacy in public” theory.

Access to Information legislation in Canada is another avenue for the public to request government information. Information obtained under Access to Information legislation is not proactively released in machine-readable formats but made available through individual requests. A transformation of this public data into open data could result in privacy violations. Such was the case when Steve Song had the idea of taking the public data of registered gun owners, mapping them, and releasing them as open data (Scassa, 2014, p. 404). The data was taken from an analogue form that required a high degree of effort to analyze, to a dataset that was easily available and allowed the public to draw conclusions on particular neighbourhoods. The map raised concerns from law enforcement officials and members of the public, who believed the data manipulation would aid burglars (“Open Data & Privacy”, 2013). Teresa Scassa (2014) argues that while information obtained under Access to Information requests are available to the public, preparing a request and going through the administrative process requires time and effort, which does not allow for the information to be shared widely (p. 403). The United Kingdom is working to streamline its Freedom of Information Act to require that all datasets released through the legislation are reusable and publically available (O’Hara, 6). Although this would lead to a greater adoption of open data, it may also lead government bodies to heavily redact information or refuse to release information they may have otherwise released in an analogue format.

The repurposing of public data as open data can violate expectations that the data custodian had factored into their original privacy assessment, and thereby open the possibility for unintended uses of the data. Helen Nissenbaum’s Contextual Integrity framework evaluates privacy on the basis of prevailing norms and expectations in relation to specific social contexts. Norms of information distribution and transmission principles are foundational to the framework, and it can be said that contextual integrity is violated if there is a breach in these norms (Nissenbaum, 2004, p. 138). Public data must be evaluated for privacy risks in a fashion similar to any other data, before it is released as an open dataset.

Privacy-enhancing Options

Open Data Procedure:

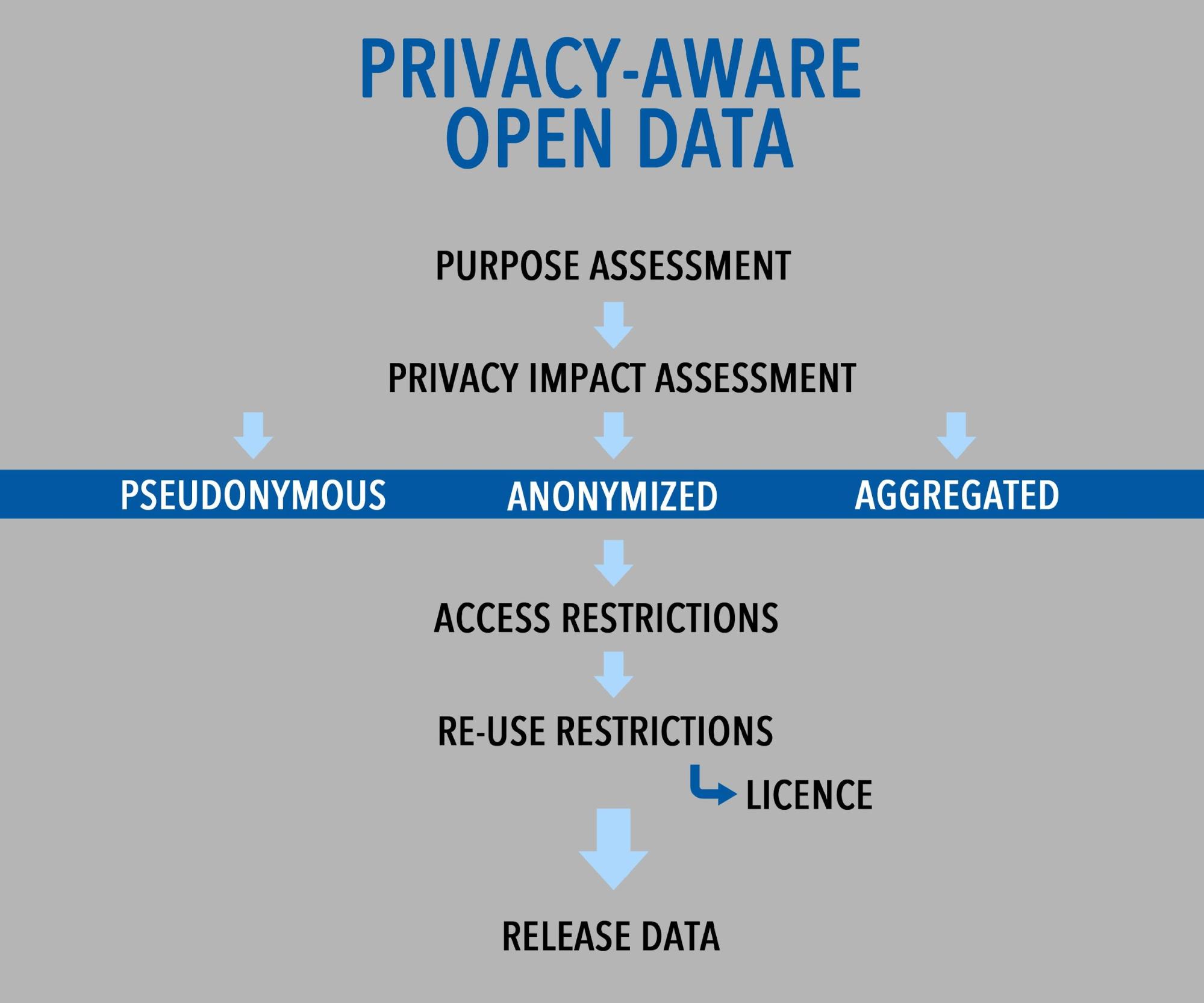

Many privacy-preserving frameworks of open data have been proposed in order to provide public sector authorities with a guideline on how to appropriately meet their open data objectives in a privacy-aware way. The competing relationship between accountability and privacy make a risk-based process a useful measure to determine the impact/tradeoff of these variables. The first procedure that governments should conduct is a purpose assessment. Governments release data as a public accountability measure, so the specific objectives of the release should be evaluated to determine that the data being released accomplishes the goal. Open data should not be released for the sake of doing so, or simply because it is part of a global trend. The second step would be to conduct a privacy impact assessment to determine the privacy implications of releasing the specific data in question. Adopting a process that includes a privacy impact assessment, including the likelihood of the data being associated with individuals, would help to mitigate the risks posed to privacy.

Particular care should be afforded to data of a sensitive nature, such as health, financial, and security information. A country may have an existing information sensitivity scale based on its prevailing norms and values. For example, Germany has recognized three categories of sensitivity that are afforded specific levels of protection; intimate, private, and individual (O’Hara, 36). A documented process that standardizes these assessments in checklists or other formal forms would help to ensure that a privacy impact assessment is successfully implemented (“Open Data and Privacy FAQ”).

Technical Tools:

In addition to the procedural steps that can be taken in order to protect the privacy of the public, there are also technical tools that are used when releasing open datasets. These tools implement varying levels of privacy into the design of the data before they are released. Given that privacy is difficult to protect after a breach has occurred, these tools play a vital role in protecting privacy in open datasets.

Pseudonymous Data:

This type of data refers to the practice whereby an individual’s identifying information is replaced with a random unique identifier. It allows the data to be unidentifiable while demonstrating that it belonged to a particular person and allowing databases to differentiate rows of information. A risk of using pseudonymous data is that it may still identify a particular individual if the data is analyzed deeply. This is possible because pseudonymous data does not remove of all personally identifiable information, but rather weakens the link to the original data subject. Another risk is the link-ability of the pseudonym, particularly if the same identifier was used in another dataset or retained by any other party (Nin, Herranz, 2010, p. 157). This could help inform the indirect identification of an individual by comparing the information with other databases where the individual is identified (Nin, Herranz, 2010, p. 158). This probabilistic method of identification is effectively how credit reporting and scoring is conducted (Pape, Serna-Olvera, Tesfay, 2015). The Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada has suggested that any method used to connect a device and its owner, such as a unique identifier, has the potential to create a detailed profile of a person’s behaviour (“Seizing Opportunity”, 3).

Anonymized Data:

Anonymization techniques are attractive because they remove all personally identifiable information in a dataset, and thereby make it impossible for a privacy breach to occur. The removal of personal information also relieves the government body from obligations and requirements under privacy law. However, a widely documented risk of anonymization techniques is re-identification of the data. Re-identification can occur when a hacker or another actor finds hidden personally identifiable information in a dataset (“Open Data and Privacy FAQ”). It could also occur through indirect-identification techniques as described above. It has also been argued that the probability of re-identification has increased due to the availability of more privacy related data in society (Pape, Serna-Olvera, Tesfay, 2015).

The Netflix Prize Data Study was a competition where Netflix released anonymized open datasets on the ratings of specific movies (Narayanan, Shmatikov, 2008, p. 8). It was demonstrated that the data could be used to re-identify thousands of users using an algorithm to trace the movie ratings to Netflix accounts (Narayanan, Shmatikov, 2008, p. 6). Although there are few cases that provide evidence that third parties have associated open data with personal information, this may be because these parties would not have an interest in sharing this practice with the public (“Open Data and Privacy FAQ”).

Aggregated Data:

Data aggregation refers to the practice where detailed data are grouped and released as statistics or metadata. This practice enhances the privacy of individuals as specific people cannot be identified when data are rolled up into pools with specific quantity thresholds. These thresholds are important because if a given pool has too few people associated with it, it could make the identity of the individual(s) obvious. However, the Privacy Act states that personal information may be disclosed “to any person or body for research or statistical purposes if the head of the government institution…(i) is satisfied that the purpose for which the information is disclosed cannot reasonably be accomplished unless the information is provided in a form that would identify the individual to whom it relates” (Privacy Act, R.S.C., 1985, c. P-21). This provision essentially allows individuals to be identified within statistics where they are required, however the Office of the Information Commissioner of Canada has identified a list of questions that should be answered before this exception is used (“Section 19 - Personal Information”, 2014). An example of an aggregated data technique is “differential privacy”, which only returns statistical responses to queries about an underlying dataset (Borgesius, Gray, Eechoud, 2015, p. 2123). A level of “noise” is added to these datasets to further protect privacy; however the uncertainty that this noise provides can be exhausted, at which point the data should not be released (Zevenbergen, et al., 2013, p. 38).

Policy Tools:

Policy can also be used as a method to protect privacy. There are primarily two policy tools that can help to protect informational privacy: access and re-use restrictions. These restrictions can only be applied in limited capacities in order for data to be classified as open, but they help situate open data within the scope of the available policy tools.

Access Restrictions:

The first way to balance privacy and open data policy is by restricting access. To achieve a particular objective that underpins open data, it might not always be necessary to allow everyone access to government-held data (Borgesius et al., 2015, p. 2122). Access restrictions can be considered as a middle ground between the two extremes of opening all data or restricting it completely. It allows the government body to maintain control of the data by imposing limits on who may access it. This access restriction could be fairly broad, such as restricting access to Canadian open data sets from individuals located outside of the country. Such a restriction may help limit the territorial issues of privacy that were previously outlined.

There are four types of access restrictions; managed, attribute-based, public, and raw data. Each type of access restriction provides a different level of privacy protection. Managed access can generally be considered as the most restrictive type of access as it only allows data to be shared with pre-determined or authorized individuals (Zevenbergen et al., p. 29). This allows for the most control over the data’s dissemination and therefore is effective in protecting privacy. Attribute-based access is less restrictive as it uses a list of specific criteria that an end-user must satisfy in order to access the data. However, the access criteria can be extensive, and thereby be used to effectively exclude specific groups. This would be contrary to the objectives of open data. Indeed, the 6th principle of the Sunlight Foundation’s 8 principles for open data requires that it be non-discriminatory, and therefore not be designed to exclude particular groups in society (“Putting the Open in Open Data”). Publicly accessible data, as addressed above, refers to data that is available to anyone, but under the terms that are not “open” (Jaatinen, 2016, p. 34). Finally, raw or open data are simply data that anyone can access and use without restriction.

Re-Use Restrictions:

The other policy tool that can be used to protect data privacy is restricting how data is re-used. These restrictions can be implemented through licenses that are attached to the data. Licenses provide the owner of the data the ability to limit how the data is distributed by those who access it. In the context of open data, the respective government body is the owner of the data and is able to use licenses or crown copyright to protect its property in Canada. As of March 11 2015, the Canadian federal government’s Open Government Licence states that anyone is free to “copy, modify, publish, translate, adapt, distribute or otherwise use the Information in any medium, mode or format for any lawful purpose” (“Open Government Licence - Canada”, 2015). The license also includes a forum selection clause, stating that “legal proceedings related to this licence may only be brought in the courts of Ontario or the Federal Court of Canada” (“Open Government Licence - Canada”, 2015). These clauses can pose risks to privacy, especially in territorial contexts. The privacy laws of British Columbia (BC) would not apply in the event where a legal proceeding involving the privacy of a BC resident was raised. Although this does not pose a significant threat to privacy within Canada, it can be a problem when forums are selected in other countries.

Property over intangible goods such as data is partly determined by copyright law. The Canadian Copyright Act awards copyright protection to datasets and databases as they meet the requirement under Section 2 for “selection or arrangement” and qualify as a compilation (Patalony, 2005, p. 219). As a result, databases cannot be copied without the authorization of the owner. However, some argue that the data collected and maintained by the government is paid for by its citizens through taxes, and therefore should be the property of the citizenry (“Datalibre.ca - About”). Crown copyright is the protection provided to government works, such as court decisions. Courts have the ability to dictate the license terms to those who publish these decisions (Scassa, 2015). Crown copyright can therefore be used to protect the privacy interests of the public by restricting the re-use of the data. Given that open datasets by definition do not have re-use restrictions in their licences, other than perhaps share-alike provisions, they often can’t use crown copyright as a method of protecting privacy. The definition of open data makes it difficult to use access restrictions in order to protect privacy. The role of the procedural and technical tools are therefore more important in protecting the privacy of data subjects as policy tools are surrendered in the interest of democratizing accessibility to government data.

An overview of the steps to consider to achieve a privacy-aware open data initiative.

An overview of the steps to consider to achieve a privacy-aware open data initiative.

References

Borgesius, F., Gray, J., Eechoud, M. (2015). “Open Data, Privacy, and Fair Information Principles: Towards a Balancing Framework” Berkeley Technology Law Journal, 30(3), 2073-2132.

Canadian Heritage. (2013). “Putting the Open in Open Data” http://www.rcip-chin.gc.ca/sgc-cms/nouvelles-news/anglais-english/?p=8815

Canadian Internet Policy and Public Interest Clinic. (2016). “Open Data, Open Citizens?” https://cippic.ca/en/open_governance/open_data_and_privacy

Canadian Internet Policy and Public Interest Clinic. (n.d.) “Open Data and Privacy” https://cippic.ca/en/en/FAQ/Open_Data_and_Privacy

Crawley, M. (2017). “Sunshine List Reveals Ontario’s Public Sector Salaries” CBC News. http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/sunshine-list-2017-ontario-salaries-2016-1.4037987

DataLibre. 2015. “Datalibre.ca.” datalibre.ca. http://datalibre.ca

Government of Canada. (2015). “Open Government Licence - Canada” http://open.canada.ca/en/open-government-licence-canada

Green, B., Cunningham, G., Ekblaw, A., Kominers, P., Linzer, A., Crawford, S. (2017). “Open Data Privacy”. Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society Research. https://dash.harvard.edu/handle/1/30340010

Hacking, I. (1990). The Taming of Chance. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press

Information and Privacy Commissioner of Ontario. (2017) “Open Government and Protecting Privacy” https://www.ipc.on.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/open-gov-privacy-1.pdf

Jaatinen, T. (2016). “The Relationship Between Open Data Initiatives, Privacy, and Government Transparency: A Love Triangle?” International Data Privacy Law, 6(1), 28-38.

Justice Laws Website. (2017). “Privacy Act, RSC 1985, c P-21” http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/p-21/

Narayanan, A., Shmatikov, V., (2008). “Robust De-anonymisation of Large Sparse Datasets”, in Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy, 111-125. https://www.cs.utexas.edu/~shmat/shmat_oak08netflix.pdf

Nin, J., Herranz, J. (2010). Privacy and Anonymity in Information Management Systems: New Techniques for New Practical Problems. London UK: Springer-Verlag

Nissenbaum, H. (2004). “Privacy as Contextual Integrity” Washington Law Review Association, 119(79), 119-158.

Nissenbaum, H. (1998). “Protecting Privacy in an Information Age: The Problem of Privacy in Public” Law and Philosophy, 17, 559-596

O’Hara, K. (2011). “Transparent Government, Not Transparent Citizens: A Report on Privacy and Transparency for the Cabinet Office” Cabinet Office. Her Majesty’s Government. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/61279/transparency-and-privacy-review-annex-a.pdf

Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada (2012) “Seizing Opportunity: Good Privacy Practices for Developing Mobile Apps” https://www.priv.gc.ca/media/1979/gd_app_201210_e.pdf

opendataresearch.org. (2013). “Open Data & Privacy” http://www.opendataresearch.org/content/2013/501/open-data-privacy-discussion-notes

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2013). “OECD Guidelines on the Protection of Privacy and Transborder Flows of Personal Data” http://www.oecd.org/sti/ieconomy/ oecdguidelinesontheprotectionofprivacyandtransborderflowsofpersonaldata.htm

Pantalony, R. (2005). “Canada’s Database Decision: An American Import Takes Hold” Journal of World Intellectual Property, 2(2), 209-220.

Pape, S., Serna-Olver J., Tesfay, W. (2015, Sept). “Why Open Data May Threaten Your Privacy” In: Workshop on Privacy and Inference, co-located with KI.

Scassa, T. (2014). “Privacy and Open Government” Future Internet, 6, 397-413.

Scassa, T. (2015, June 23). “Privacy and the Publication of Court Decisions: The Privacy Commissioner Weighs In” Teresascassa.ca. Web. http://www.teresascassa.ca/index.php?option=com_k2&view=item&id=188:privacy-and-the-publication-of-court-decisions-the-privacy-commissioner-weighs-in&Itemid=80

Zevenbergen, B., Brown, I., Wright, Joss., Erdos, D. (2013) “Ethical Privacy Guidelines for Mobile Connectivity Measurements” Oxford Internet Institute, 1-41. https://iapp.org/media/pdf/knowledge_center/ Ethical_Privacy_Guidelines_for_Mobile_Connectivity_Measurements.pdf